Film Review: PSU Belly Read and Belly Counter Speed Option

Against Michigan, Penn State pulled out a nice wrinkle to their run action. While most teams that run out of gun incorporate an inside zone read, the Nittany Lions prefer more of a belly read approach. In this post we are going to look at the difference between the more common Inside Zone run, the Belly Option that PSU prefers, and the counter action off of it with the utilization of a speed option. A couple weeks later Rutgers tried to utilize a similar strategy but had much less success. We're going to poke at the difference between teams in this post as well.

Inside Zone Read vs Belly Read

First, here's Rutgers running (split) inside zone read.

Formation Tweeks

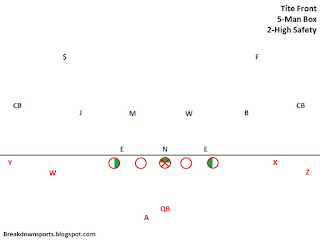

The first thing I want to show you is two screen shots, one from the Rutgers offense and one from the Penn State offense (we are going to compare the two a little bit throughout this article.

Notice that both RBs are lined up with 6 yards depth. The difference is the alignment of the QB. PSU keeps their QB at 6 yards, whereas Rutgers lines their QB up at about 5 yards depth.

So for Rutgers, the mesh point is at 5 yards in the backfield. For Penn State, the QB steps forward post snap, and the mesh starts at 5 yards but the mesh isn't completed until the ball is only 3 yards from the LOS.

There is a reason both teams do what they are doing. For Rutgers, this slight offset between QB and RB is common throughout football, particularly for teams that want to use inside zone. The offset allows for a more downhill angle to run the inside zone and minimizes the movement of the QB post snap (allowing him to focus more on his reads).

In contrast, by aligning the RB with more depth, you are tipping your schemes. Stretch away from the RB's alignment becomes extremely difficult, as does Power Read. So allowing this movement to happen post snap mitigates that pre-snap tip. The longer mesh point forces the read defender to commit prior to making the read, however, it also means the eventual ball carrier takes longer to have the ball in his hands and start making plays (remember, one of the keys to inside zone is to get the ball as deep as you can).

To make the point clearer. PSU does run Inside Zone as well. Watch McSorley's footwork here and notice he doesn't come downhill at all, but instead stays mostly flat (he does shuffle backwards to modify the mesh point a little).

Just a little bit of counter action wiped out the entire LB level of the defense, because it's the same initial look (it's gap blocking now, but the motion is the same as inside zone, and the backfield footwork looks like Belly Read).

But now let's look at Rutgers try to do the same thing a week later. The inside zone run doesn't entice the same reaction from the defense. The mesh point is further back, the QB's footwork is slow and non-threatening. It doesn't press the LOS, in fact, the first few steps for a play action are generally the same. Can it work? Absolutely, but you better be having big success on your inside zone run first (note: Rutgers was not having major success on inside zone prior to this, but neither was PSU having success running their Belly Read play; caveats apply for the basic threat of Barkley vs any other RB).

Inside Zone Read vs Belly Read

First, here's Rutgers running (split) inside zone read.

Here's PSU running the Belly Read

Formation Tweeks

The first thing I want to show you is two screen shots, one from the Rutgers offense and one from the Penn State offense (we are going to compare the two a little bit throughout this article.

Notice that both RBs are lined up with 6 yards depth. The difference is the alignment of the QB. PSU keeps their QB at 6 yards, whereas Rutgers lines their QB up at about 5 yards depth.

So for Rutgers, the mesh point is at 5 yards in the backfield. For Penn State, the QB steps forward post snap, and the mesh starts at 5 yards but the mesh isn't completed until the ball is only 3 yards from the LOS.

There is a reason both teams do what they are doing. For Rutgers, this slight offset between QB and RB is common throughout football, particularly for teams that want to use inside zone. The offset allows for a more downhill angle to run the inside zone and minimizes the movement of the QB post snap (allowing him to focus more on his reads).

In contrast, by aligning the RB with more depth, you are tipping your schemes. Stretch away from the RB's alignment becomes extremely difficult, as does Power Read. So allowing this movement to happen post snap mitigates that pre-snap tip. The longer mesh point forces the read defender to commit prior to making the read, however, it also means the eventual ball carrier takes longer to have the ball in his hands and start making plays (remember, one of the keys to inside zone is to get the ball as deep as you can).

To make the point clearer. PSU does run Inside Zone as well. Watch McSorley's footwork here and notice he doesn't come downhill at all, but instead stays mostly flat (he does shuffle backwards to modify the mesh point a little).

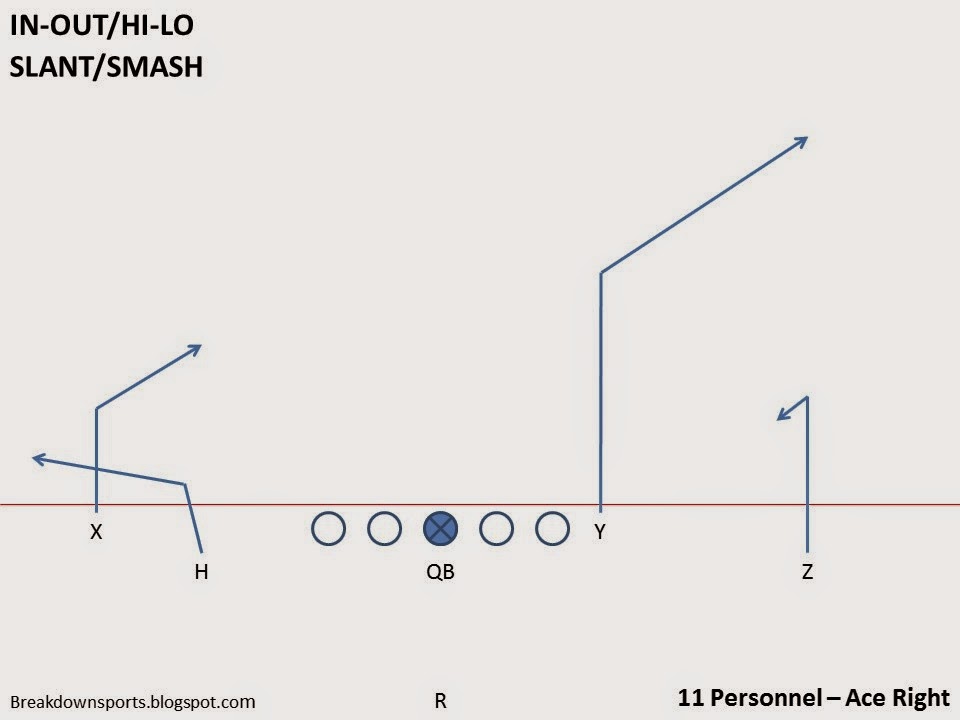

What's the deal with the Belly?

Up front, every thing is the same for the offensive line. Both runs are essentially Inside Zone blocking with the backside unblocked as the read defender. The difference is generally the mesh point and how the defense is attacked because of it.

The initial track of the RB is going to generally be the back foot of the center (rather than approximately the backside foot of the playside guard as it is for inside zone). He's generally going to read the center's block (0-tech to 1-tech away from the RB's alignment) and his first cut will be made off of that read. His second read will be the defender further backside or further inside of the Center's block. All of this should sound a lot like Inside Zone in a number of cases. But depending on the defense's alignment, the rules do change slightly.

In general, what this does is move the aiming point one gap further toward the RB's alignment than Inside Zone would. Typically, Penn State likes to utilize this to attack 0- or 1-technique DTs.

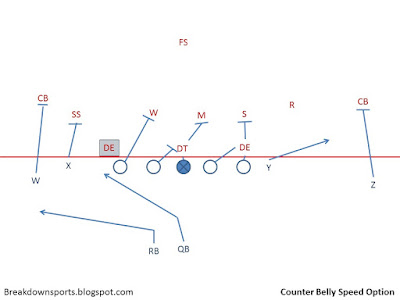

Speed Option Counter

Like the original Belly play out of veer, the Belly read forces the LBs to crash down inside hard, otherwise you can get gashed quickly. With the mesh point moving so close to the LOS, the LBs need to be prepared to fill holes made by the zone blocking and form a wall at the LOS. But this threat forces a reaction, and that reaction is why the Speed Option out of the Belly Read look is so threatening.

Here's the speed option look. Notice both the QB and RB's first step is similar to the Belly Read, and watch the LB's reaction to this as they attempt to fill down and form a wall at the LOS.

Just a little bit of counter action wiped out the entire LB level of the defense, because it's the same initial look (it's gap blocking now, but the motion is the same as inside zone, and the backfield footwork looks like Belly Read).

But now let's look at Rutgers try to do the same thing a week later. The inside zone run doesn't entice the same reaction from the defense. The mesh point is further back, the QB's footwork is slow and non-threatening. It doesn't press the LOS, in fact, the first few steps for a play action are generally the same. Can it work? Absolutely, but you better be having big success on your inside zone run first (note: Rutgers was not having major success on inside zone prior to this, but neither was PSU having success running their Belly Read play; caveats apply for the basic threat of Barkley vs any other RB).

The counter step forces a mirror step from the Michigan LBs, but that's it. Yes, the threat from either backfield player is significantly less from Rutgers than PSU, but PSU would have scored a TD with basically any Big Ten RB with the success they had on their option play.

Furthermore, the threat of the Belly Read allows this Speed Option Counter to basically nullify a struggling OL. While PSU had put up yards on the ground, it largely was despite a struggling offensive line. The first long run was dead to rights on the playside, only for Barkley to make a great cut and a backside defender to bust an assignment, but the blocking was mediocre at best. PSU was able to scheme plays to limit the impact of the DL vs OL matchup against Michigan. However, it should be noted that once on film, they struggled to do much of the same against OSU and MSU in the following weeks. You can only do so much to hide a struggling OL (which remains PSU's Achilles heal on offense).

Comments

Post a Comment