Inside the Playbook: Wisconsin Lead Power O, Power O, and Counter with F/H Part I

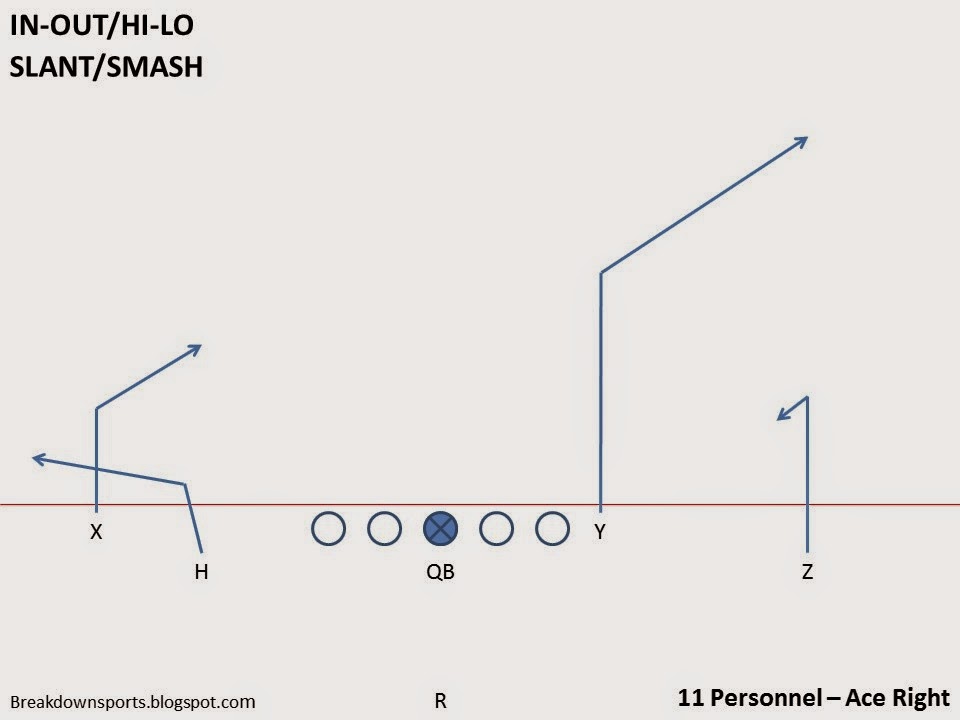

In this post, we are going to look at how Wisconsin utilizes

the Wing to run Power O. Wisconsin will utilize 12 personnel most often, but

will also sprinkle in 11 personnel or even 13 personnel to run this play. And

while they can still run a traditional, I-Form Power O, I want to focus specifically

on what they do with a TE off the LOS, and how they utilize that as well as

anyone in college football to add a blocker from the backside, and insert him

at the point of attack.

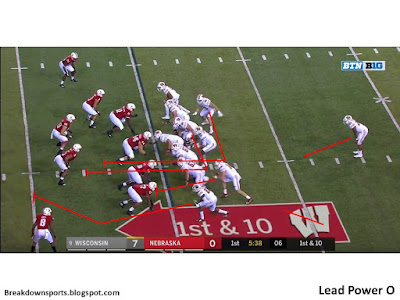

Dos Lead Power O

Let’s start with the formation we are focusing most on, the

Dos formation. Here, you have double twins bunched tight to the LOS, effectively

putting 9 offensive players balanced on both sides of the football near the

LOS. The balance of the formation allows them to run it right or left without

changing anything. The splits of the formation allow them to run it to the

boundary or the field, again, with hardly changing the look (though defenses

will often play boundary/field differently due to how they must cover space).

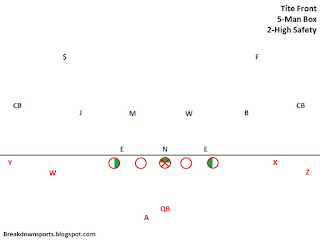

Now, I’m going to link a few examples. One thing you will

almost certainly notice is that, sometimes it looks like Power O, sometimes it

looks more like Counter H. It really is Lead Power O, but there are many

adjustments that can be made on the front side by the two receivers. First, let’s

look at a diagram to help explain.

That Backer (B) won’t always be lined up outside the U.

Sometimes he will line up between the U and the PST. That CB won’t always be

aligned near the LOS, sometimes he will have more depth. All this means is that

there isn’t always a “kickout defender” immediately threatening, and that can

results in both the U and X down blocking. If a leverage defender appears, it

may mean that’s the player the BSG takes, even if it means kicking him out, a

la a Counter H. But all these adjustments are made based on how the defensive front

aligns, not with the play call itself. These adjustments can be based on

communication, or can be based on scouting (if a CB sucks in run support, why

waste a blocker on him?).

Here’s a first play, where both the U and the X are going to

kick out players aligned outside of them.

Another example:

And here’s another example of a play with a kickout.

And here, there is no force defender immediately available,

so again, everyone down blocks.

Now is a little wrinkle that I want to spend some time on. Back

in the late 80s to early 90s, the wrong arm technique became kryptonite for

teams trying to kick the EMOL with Power or Counter (at the time, the favorite

was Counter OT). This wrong arm served two purposes: 1) it got the EMOL further

inside, not allowing the RB to get to the C gap or even B gap, and constricting

the run options; and 2) it often picked off the lead blocker following the kick

block, causing a pile-up right at the point of attack. And it was really a

mess. So here is what football coaches did:

First, they stubbornly did what stubborn football coaches

always do, they told their kick blockers to toughen up and root that defender’s

ass out of there. And OGs and FBs having the mentality they had, swore up and

down that they could root that defender’s ass out of there. They couldn’t.

Second, they discussed “logging” the defender. This effectively

means, rather than aiming at the defender’s downfield (the direction the

offense is going in) shoulder, they instead aim at the defender’s upfield (the

shoulder opposite the offense is going in) shoulder and roll (or log) around

the defender and seal him back inside. But coaches are a little hesitant to do

this, it’s more fancy footwork and less manly. And frankly, it’s really, really

tough. It’s tough for an OG to see the wrong arm coming, adjust his attack, and

make that play. And if the EMOL doesn’t run wrong arm, now you’re out of

position and the play is blown up. So…

Third, have the kickout defender run right past him. Give

him a little shove on the way, but if that guy wants to take himself out of the

play let him. Just give him a shove and keep moving to the second level. The “lead”

puller then has more time to adjust to this technique, and if he becomes a

backfield threat, he is the one that can log him.

Here, an edge defender comes flying inside, and the OG just lets

him go for the backside lead blocker to clean up. This is an example of how

Lead Power O is essentially a merging of Power O and Counter H, and how

adjustments from both of those plays can be utilized with this play.

It is also apparent that Wisconsin believes in the idea of “blocking

the greatest threat”, meaning, why block CBs when you can block more

threatening safeties.

Comments

Post a Comment