Inside the Playbook: Cover 4 Safety Play

The aspect of MSU’s defense that gets the most focus is

undoubtedly the CB position. Fans and media folk love to point out the fact

that the CBs are often left on an island by themselves, remaining hip-to-hip

with their receiver from the snap of the football to the play is dead. But it

is my opinion that CB may not even be the most important position in the

Spartans Cover 4 secondary. In fact, it is the safeties that are consistently

taxed mentally, pulled between run support and coverage. While CBs receiver the

brunt of the bait, the safeties are left with the largest quandary. It has long

been my opinion that, at the heart of attacking MSU’s defense, lies attacking

the safeties. Unfortunately for teams facing the Spartans, Michigan State’s

safety rarely make that an easy task either.

Standard Cover 4 Pass

Support

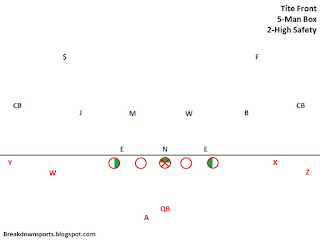

To start the play, MSU is generally going to align their

safeties between 7-9 yards off the LOS. Their eyes will work toward the #2

receiver. If the #2 receiver is split off the line, the safety will generally

align about 9 yards off and two yards inside. If the #2 is connected, the

safety will align about 9 yards off and 2 yards outside. If the #2 is a RB, the

safety will align approximately 9 yards off and 2 yards outside the EMOL,

working his eyes through the EMOL to the backfield.

#2 on LOS

Let’s first assume that the #2 is on the LOS. The safety

will be looking to see if the #2 is working vertical in a route. If #2 reaches

7 yards, the safety will pick him up in coverage. If the #2 works immediately

inside or outside short, he will be the OLB’s responsibility, and the #2 can

focus on working over the top and inside on the #1, helping the CB in coverage.

In this clip of MSU vs Michigan, Funchess is aligned tight to the LOS as the #2 in the formation. He'll run a vertical release, and the safety will pick him up, maintaining inside leverage. That inside leverage puts him in position to crash down on the post route and get the PBU.

In this clip of MSU vs Michigan, Funchess is aligned tight to the LOS as the #2 in the formation. He'll run a vertical release, and the safety will pick him up, maintaining inside leverage. That inside leverage puts him in position to crash down on the post route and get the PBU.

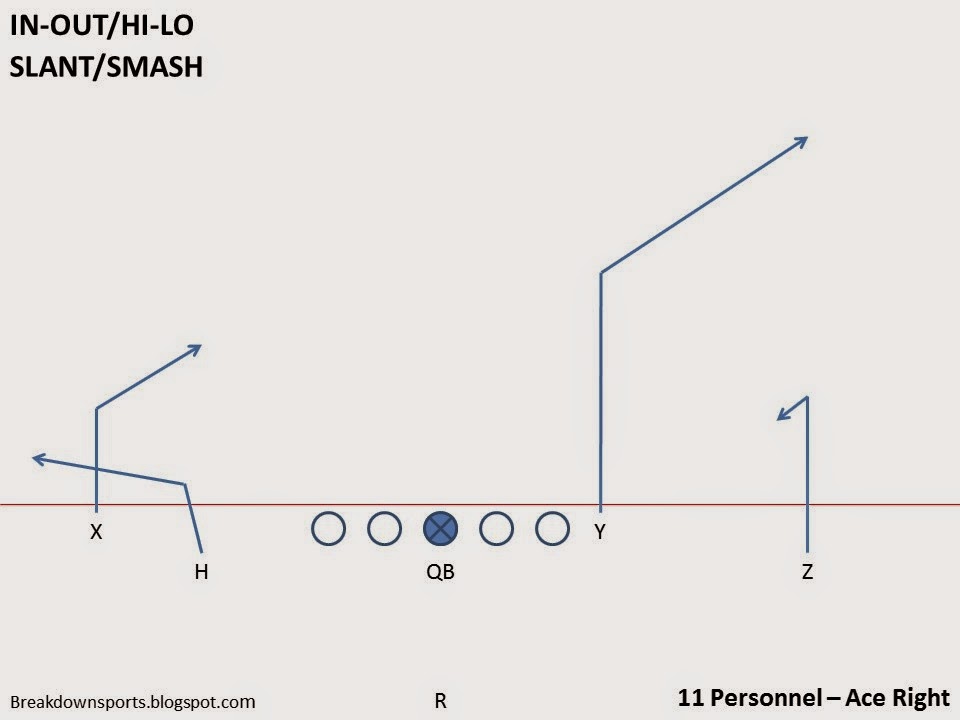

#2 Behind the formation

If the #2 receiver to the safeties side is a RB, the safety will work his keys through the EMOL to the RB. The EMOL should be a strong give away whether the play is run pass by how he moves at the snap. In this case, it is unlikely the RB will be able to threaten vertical, and instead will be picked up by the OLB. At that point, the safety will be looking to help over the top of #1, while keeping a keen eye toward the far side of the field, expecting any deep crosses coming from that direction. The primary exception to this rule would be on the ever deadly wheel route, in which case the safety needs to be especially cognizant off of play action.

#2 Working the Screen

If the #2, either a WR on a bubble screen or a RB on a quick

swing pass, works immediately outside, the safety must immediately take his

eyes outside to the #1. The CB will replace the safety as the outside leverage

defender (similar to a crack exchange) while the safety takes care of any slip

block that a receiver may try.

In this clip, the CB doesn't make the tackle, but the point is still the same. The #1 immediately works inside on what looks like a shallow cross. The CB then takes his eyes to the #2 and then to the backfield. The shallow cross makes the slot receiver the effective #1, so the CB starts to carry him, but as that receiver works vertical and the RB flares outside, the RB then becomes the #1. And it is the CB coming late into the play. The safety has picked up the "slip block" receiver. Instead, he's really trying to crack a LB inside.

In this clip, the CB doesn't make the tackle, but the point is still the same. The #1 immediately works inside on what looks like a shallow cross. The CB then takes his eyes to the #2 and then to the backfield. The shallow cross makes the slot receiver the effective #1, so the CB starts to carry him, but as that receiver works vertical and the RB flares outside, the RB then becomes the #1. And it is the CB coming late into the play. The safety has picked up the "slip block" receiver. Instead, he's really trying to crack a LB inside.

Standard Cover 4 Run

Support

There are two separate assignments for the safety in run

support: run to and run away.

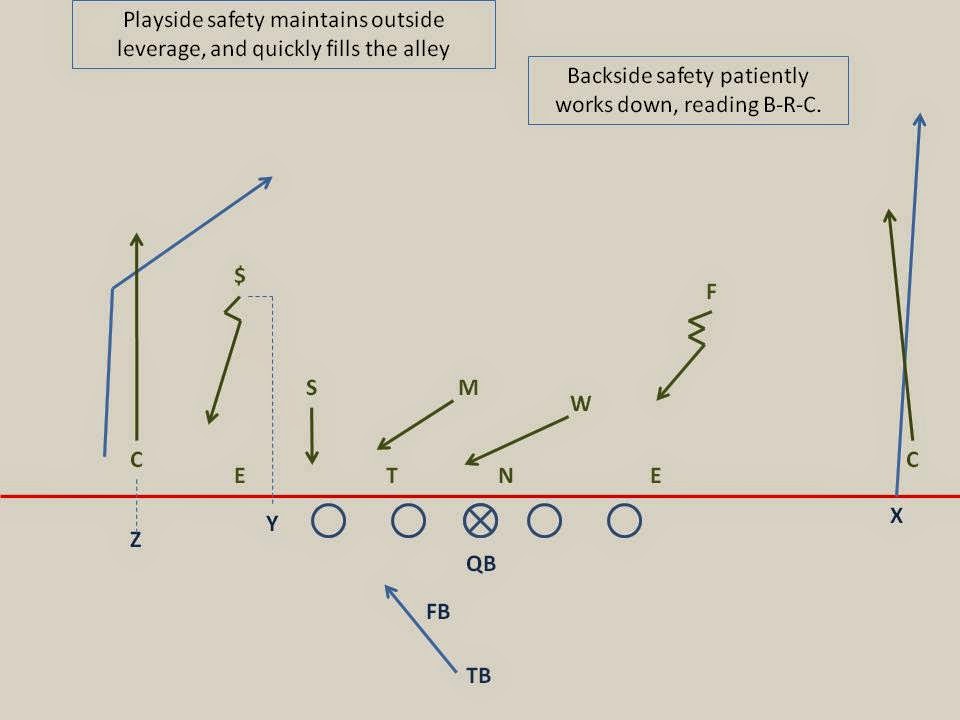

Run To:

If the flow of the play is toward the safety, it will be his

task to fill forward in the alley and he must fill forward immediately (he is

the force player). The alley is the part of the field between the EMOL and the

detached receiver. It is important that the safety maintain his outside

shoulder free, as he cannot allow the runner outside of him. Maintaining a

relation with his helmet playside of the ball carrier, he will force any play

that bounces outside to work back to the inside. By doing this, he effectively

creates a new sideline (nothing can be run outside of him), therefore reducing

the width of the field and allowing his support work from the inside outside as

they chase.

Here's a situational play that sees the safety creeping even closer to the LOS. It's a quick toss with outside zone pin-and-pull blocking. See how the playside safety quickly fights down to fill the alley. While the play never does bounce outside, the safety has maintained proper relationship and would have forced everything back inside.

Here's a situational play that sees the safety creeping even closer to the LOS. It's a quick toss with outside zone pin-and-pull blocking. See how the playside safety quickly fights down to fill the alley. While the play never does bounce outside, the safety has maintained proper relationship and would have forced everything back inside.

Run Away:

If the flow of the play is away from the safety, he must

patiently “screw” down to the LB level, about above where the EMOL initially aligned.

B-R-C. Boot, reverse, cutback.

Those are his responsibilities on the backside. The LBs in the defense are allowed to fast flow, and it’s because of this safety that they are able to play so downhill and fast.

B-R-C. Boot, reverse, cutback.

Those are his responsibilities on the backside. The LBs in the defense are allowed to fast flow, and it’s because of this safety that they are able to play so downhill and fast.

With run away from him, the backside safety first must look

for any action coming back his way, either from the far side in the form of a

receiver or TE, from an OG pulling in pass pro, or leaking out FB out of the

backfield. Once the boot is read, the backside safety will look to rob any

crossing routes. To do this, he must first work backwards in case any receiver

is trying to get behind him. If he gets too flat, there will be open space

behind him. Once he’s ensured he’s deeper than deepest man coming back across,

he can then work down toward the flat.

Here's a video of a safety doing a poor job on the "boot". While OSU doesn't boot, the action is heavy away, so this is the same responsibility for the safety. Here, he screws down to take away the cutback (in this case, the counter trey or inverted veer), but he gets too far forward and then starts working horizontally before taking his eyes to his key. Because of this he is late, and he gets beat over the top.

Here's a video of a safety doing a poor job on the "boot". While OSU doesn't boot, the action is heavy away, so this is the same responsibility for the safety. Here, he screws down to take away the cutback (in this case, the counter trey or inverted veer), but he gets too far forward and then starts working horizontally before taking his eyes to his key. Because of this he is late, and he gets beat over the top.

The next read is the reverse. Now that the handoff has been

read, the backside safety must make sure that no ball carrier gets outside of

him. Again, he must be patient because of the boot, but now also must make sure

he doesn’t screw too far inside. He is the backside force player, he is the new

effective sideline on the backside, he is reducing the width of the field. When

the safety sees reverse (often times from a pulling OL, or more often an OT

loop blocking back and cracking any reverse flow) he will work laterally, or

even a little backward, to maintain his relationship outside of the reverse

ball carrier.

Lastly, cutback. Once it is determined the play isn’t a boot

back his direction or a reverse, he can start squeezing inside and preventing

any cutback play. Again, as the LBs flow fast to the ball, one of the biggest

threats is a quick cutback. By allowing the LBs and the backside DE to chase,

they can better stop the nominal play, trusting the backside safety to make

take of any cutbacks.

This zone read works similar to a reverse in many ways. In this case, the backside safety is patient working down the the LB level, and then doesn't allow the QB to escape outside of him.

Obviously, there is more to playing safety than even this, but you start to see how important it is for the safety to appropriately and quickly make his correct reads to be effective in this defense. Narduzzi and Co can make adjustments to simplify these reads (last year, the field safety often took the #2 from the snap if the release was vertical or outside, allowing the OLB to remain in the box), but it is still fundamental that the safety is consistently sound, otherwise they potentially give up the big play. This is why I’ve long advocated that the safety should be the position that offenses try to attack, because they have so much on their plate, and when they make a mistake, it leads to big plays for the offense. Unfortunately for opposing offenses, MSU’s safeties rarely make these sorts of mistakes.

This zone read works similar to a reverse in many ways. In this case, the backside safety is patient working down the the LB level, and then doesn't allow the QB to escape outside of him.

Conclusions

Good safety play in the Cover 4 is all about pre-snap communication, post-snap feel, and probably most importantly, eye-discipline. Lack eye-discipline, and you'll give up a big play. That is why teams don't just trot out a cover 4 similar to MSU, and it's why MSU spends so much of their waking hours perfecting this one coverage. When handled correctly, it can provide tight coverage and a quasi-9-man box against any offense. But when offenses effectively use eye-candy (pre-snap motions, unconventional releases, misdirection, play action) they can potentially find ways to cause confusion in the backfield and spark a big play. That is why the Spartans rep this defense so hard though, so they see every possible scenario and know how to properly adjust and communicate to effectively run their defense. And it can all hinge and pivot from awful to great by the play of the safeties.Obviously, there is more to playing safety than even this, but you start to see how important it is for the safety to appropriately and quickly make his correct reads to be effective in this defense. Narduzzi and Co can make adjustments to simplify these reads (last year, the field safety often took the #2 from the snap if the release was vertical or outside, allowing the OLB to remain in the box), but it is still fundamental that the safety is consistently sound, otherwise they potentially give up the big play. This is why I’ve long advocated that the safety should be the position that offenses try to attack, because they have so much on their plate, and when they make a mistake, it leads to big plays for the offense. Unfortunately for opposing offenses, MSU’s safeties rarely make these sorts of mistakes.

Great article. Thank you. Go Green.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

Delete