Inside the Playbook: Defending the Speed Option with a Two-High Defense (BDS Exclusive)

Last time we looked at how Michigan attempted to stop Nebraska’s speed option attack with a Cover 1. Not finding much success, the

very next week, facing Northwestern, they turned to more two-high coverages in

the face of the Kain Colter lead spread attack. In this post, we’ll look at how

Michigan utilized a two-high man under and Cover 4 to defend the speed option.

How the Speed Option

is Run

Be it under center or from the shotgun, the speed option is

essentially the same. The offensive line, in the case of most modern day

offenses, will run their standard outside zone blocking scheme. The one

difference is that the offense will bypass the defense’s EMOL toward the play

and instead work to the 2nd level. The defender left free with be

the option defender, the player that the QB will read to determine if he will

keep the ball and run it himself or pitch the ball to his RB.

Here is how it looks:

Northwestern will also occasionally run a true triple option

from the pistol. To the pitch side, it is run similarly to the speed option,

with the “dive” portion of the triple option acting as the seal block to the

pitch side. Here’s how it looks:

Defending the Speed

Option with a Two-High Defense

While the man under defense and a cover 4 defense have their

differences in coverage, they are very similar in terms of how they are used to

defend the option. In both cases, the defensive EMOL, who will also be the

pitch read defender, will have QB responsibility. Often times the rest of the

DL and likely a backside LB will also flow to the QB. The safeties, meanwhile,

will be responsible to sprint down the alley and take the RB. The frontside LB

and likely any coverage defender will also support the effort.

So, responsibility goes to

RB: Safety, frontside LB, coverage

QB: EMOL, DL, backside LB.

EMOL

The EMOL, typically a DE, has QB responsibility. Because the

rest of the team is in pursuit, a cut back against the grain is potentially disastrous.

At the snap he must square up to the QB and squeeze as tight as he can into the

player next to him, making sure to leave no run lane inside of him. He doesn’t want

to gain depth or width, but let the QB come to him in a good, fundamental,

break down position. As the QB approaches, you must keep proper relation so

that you are even with his playside (outer most) number by strafing. If he

finds it useful to close the gap before pitching the football, make him not

want to do that.

Safety/OLB

The responsibility of the safety and outside LB will depend

on the coverage, formation, and checks within the coverage. Ideally, however,

you will always have a force defender preventing the play from escaping

outside, and an alley fill defender responsible for the RB from inside to

outside.

Man Under Defense

In man under, the safety can attack the alley immediately as

he sees the QB take his initial step to run the speed option. The man coverage

underneath should be able to cover the receiver, especially as the QB’s run to

the outside restricts the amount of throws he can make. Once the coverage over

the slot feels the run, they will stop and anchor without outside arm free.

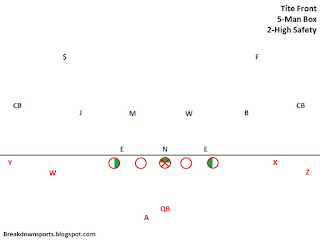

In this case, Michigan is facing Northwestern in 2013 and is

actually in a three man down front. They have one of their LBs lined up over

#2, with 2 ILBs and 5 DBs. Each of the CBs are lined up in man with both

safeties lined up over the top.

At the snap, the DE shoots up, squares to the QB, and

squeezes in to give no inside run lane to the QB. The LBs are working from

inside-out over top of the zone stretch scheme from Northwestern, and the

Michigan MIKE is able to beat the Northwestern OL to the spot. The CBs and

split LB all take inside leverage and force the WRs outside of them, who then

work to carry the defenders deep. The playside safety is crashing down

immediately with no necessary pass responsibility, and the backside safety is

rotation to the playside.

A poor angle from the safety, who has his MIKE and the pitch

defender in pursuit from inside-out, allows the RB to escape outside of him.

With the WRs in man coverage, their back is to the football, and once the RB

gets outside he has room to run before pursuit catches up to him.

Cover 4 with OLB in

the Box

In Cover 4 it will change based on how the defense wants to

use their OLB to the option side. Against a twins package, if the OLB stays in

the box, the safety must respect the immediate seam from #2 and give time for

the backside safety to rotate across. In this case, he may strafe playside to

maintain proper relation with the RB but momentarily keeping the distance

closed on #2. The stem of the #2 WR in this case can give hints about the

intention of the play. In this case, you’ll likely also adjust your DE position

to be more heads up on the offensive EMOL and protect the OLB so that he, too,

can have RB responsibility. In this case, because the OLB is pursuing

inside-out, the safety must make sure he allows no runner between him and the

sideline, keeping his outside shoulder free.

Cover 4 with Apex OLB

If the OLB was in an apex position – a position half way

between the offensive EMOL and the slot – he must be careful to recognize if

the offense is treating him as the EMOL or not. To do so, he must look through

the offensive EMOL to the football. If the offensive EMOL blocks the DE, the

OLB must squeeze inside, square to the QB, and make sure not to allow him

inside of him. In this case, the safety must take the RB, but again, cannot

allow the slip before rotation. So upon seeing the option present itself, he’ll

jump outside and maintain outside leverage on the #2 WR and allow the backside

safety to rotate, all while maintaining relation with the RB and breaking once

the offense is committed to the option run.

Here we see Michigan State taking on Nebraska in 2013 where

MSU aligns their OLB to the field in an apex position. The safety aligns 7

yards off the LOS and 1 yard inside the #2.

At the snap, you see the playside DE slanting inside. This

is because with the LB in the apex position, the DE actually has the B gap,

whereas the OLB takes the C gap. This slant actually confuses some of Nebraska’s

blocking scheme a bit, though it isn’t yet detrimental. Which you can note is

that the safety does not attack down at the snap, instead, he strafes (more

stands still) reading the #2, unconcerned with the backfield and making sure

this isn’t a pop pass off of option action.

The OLB then fights to maintain his relation with the RB,

working inside-out. The safety also is working inside-out, and has outside leverage

on the RB. But because he must respect the pass, he’s a bit late, and here’s

where the slant inside has messed up Nebraska’s QB’s read.

As Nebraska’s QB attacks MSU’s OLB, the OLB never gets

outside leverage, but does control the Nebraska WR and fights back inside. The

QB doesn’t pitch, and instead keeps for a short gain.

Cover 4 with Split

OLB

In this case, the OLB is split out wide. He will work to

maintain his outside leverage on his receiver (he is playing a zone in the

flat, so his help in pass coverage will tend to be from the zones of the LBs

inside of him, so an outside shade is appropriate in coverage too). He will

anchor down, keeping his outside shoulder free and allowing no one outside of

him. The frontside safety, with less quick pass responsibility due to the OLB

rerouting any seam and therefore allowing the backside safety time to rotate,

can now shoot down immediately upon an option look to attack the RB.

Here you see Michigan facing Northwestern in 2013.

Northwestern is aligned with a trips formation, and Michigan responds with

putting the SAM over the #2 to the option side.

On the snap, you see the defense react to the speed step

from QB. The SAM begins jumping outside #2. Meanwhile, the playside safety comes

crashing down immediately. SAM can reroute the #2 and hold him down and the

backside safety can rotate over in plenty of time to take anything deep from

#3. As soon as the EMOL is obviously left free, it is known that it is a run

rather than a pass and so the defense can get into their run defense. Note how

the DE is square to the QB and restricting the gap inside of him so that the QB

has no choice but to pitch.

The MIKE is coming from the inside out and fighting to get

over the top. By now, the SAM has anchored down and doesn’t allow the WR to

move him. This anchor constricts the run play. At this point the safety is free

and in the backfield, he has a defender with clear outside leverage outside of

him, and the pitch key DE is pursuing from inside-out.

Cover 4 to Knob

Against any knob formation – where the formation is closed

with a TE with no WR outside of him – a cover 4 will adjust to a cover 6, which

is Cover 2 on the knob side of the formation and Cover 4 away from it. In this

case, with a DE still aligned outside the offensive EMOL, he will be the read

defender. The defense will have “cloud” force, meaning the CB cannot allow

anyone outside of him. That means the CB has RB responsibility. The safety, for

his part, must make sure the TE doesn’t slip a block and attack the seam, but

then can pursue inside-out to the RB.

Here’s a video of Michigan, again against Northwestern (in2012) running a Cover 4 against a knob. In this case, Michigan flipped their CB

and Safety to have Sky leverage rather than Cloud leverage (in my opinion, this

is something that should be done more, as safeties are stronger at holding the

point and better at filling, Boundary CB can then match up against any releasing

TE downfield, but the CB has to do better at filling down than done here).

At the snap you see the DE come forward, not gain too much

depth, and get square to the QB, forcing him to pitch the football. LBs are

pursuing inside-out, while the SS in “Sky” support is beginning to attack down

on the LOS. The CB over the top is taking a useless angle that provides little

help in run support, rather than filling down into the alley.

The SS has jumped outside the TE coming out to block him.

The TE, in this case, is successful washing the Safety down and to the

sideline, which further opens up the running lane for the RB. The outside zone

blocking scheme from Northwestern also manages to get out into the MIKE LB, who

does a poor job with his hands and easily gets cut. This is all well by

Northwestern, but again we point to the awful angle from the CB crashing down

as not filling the alley at all. The DE is pursuing from behind.

With the SS washed out and the poor angle by the CB, a clear

run lane in the alley opens up and doesn’t allow pursuit to get home. From

there it’s just the RB making that CB look even worse.

Conclusion

So as you can see, the basic set up for defending the speed

option has slight tweaks within the two-high schemes, but also is quite

different than what we saw with a Cover 1 defense. A two-high defense tends to

be a bit more natural in covering the speed option, as the QB, who is keying on

the EMOL, is defended by the EMOL, and the players that have better angles get

to use those angles to defend the pitch man. Still, it isn’t without its

weaknesses, and if the defense is undisciplined it will get beat, either over

the top of speed option looks, or with the speed option itself.

Comments

Post a Comment