Inside the Playbook - Michigan's Counter Game - Part 3: Execution and Technique

We've now had an opportunity to look at the general scheme and various run tags Michigan deploys, as well as how they can modify things post-snap. But as any football coach will tell you, all the scheme in the world can't make up for poor execution. Michigan, in their run game, was a well oiled machine. It was clear on film that they were well coached and I want to take a look at some of that now.

RB Footwork

One of the items I noted early in the season was that Michigan's "Counter" did not actually feature counter footwork. Instead, Michigan deployed a much more down hill attack.

Each has benefits. Counter footwork serves as a way of having some misdirection in the backfield. It also forces the RB to pause briefly putting some separation between himself and his pullers so that he can read how they are executing their assignments and work off those blocks.

But Michigan ran their footwork much more similar to Power. As I've talked about in my Power series, in modern football, most teams Power runs have become A-to-B-to-C-to-D gap runs. If the A-gap is open, you hit it, if not, you move to the B-gap, etc. Michigan took this approach to Counter and was able to almost eliminate any TFL or zero yard gains.

My initial criticism:

One thing I don’t like is the footwork Michigan uses on Counter. Makes it hard for RB to read the wrap. It results in high efficiency (more down hill attack) but I think leaves some explosives on the field pic.twitter.com/Na2uXukc8S

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) October 18, 2021

Why Michigan does what it does:

I said my *opinion* on kick footwork on counter. But here’s an example of why you use it. A 1-2 yard gain turns into 5-6 yards, and maybe by the 2nd half into the third level. No opinion is gospel. pic.twitter.com/hhVRMgAskd

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) October 18, 2021

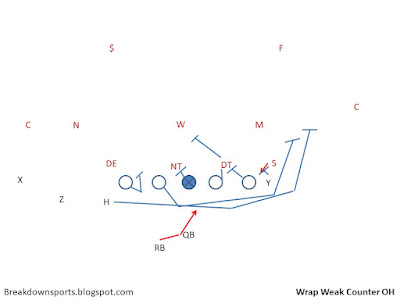

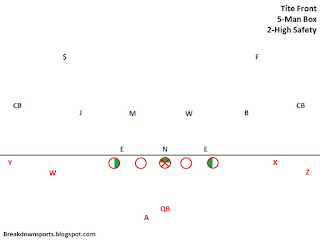

Primary Front Side Combo Blocks

On gap schemes like Counter and Power, there are two primary types of combination blocks. Those blocks are called a Trey Block (TE-OT block a first level player and one leaves to a backside LB).

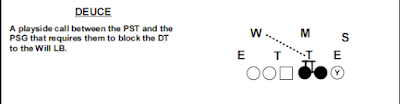

And a Deuce Block (OT-OG block a first level player and one leaves to a backside LB).

Generally speaking, the blocker that stays at the first level will be called the "post" blocker. The one that climbs to the second level will be called the "seal" or "drive" blocker.

Like any things that can be done, there are a million ways to skin a cat. I'm not going to get into how everyone teaches this combination technique. What I will emphasize are what are fairly commonly excepted items that will happen to execute a good combination block.

First, your combination block needs to get effectively hip-to-hip. For some this is thigh to ass crack. But the point, to be clear, is that there is no space between the two blockers as they engage the first level blocker. The absolute worst thing that can happen is a down defender splitting in between a combination block.

Second, if at all possible, we want to take the down defender (who is often aligned between the two blockers at the snap) and displace onto the inside of the inside blocker. This means on a Deuce Block, for instance, we want the Tackle to help push the down defender to the inside shoulder of the Guard, and then have the tackle (or outside blocker) release to the second level.

Now, there are a few schools of thought on how to do this, and the right method for you depends on your system. For instance, some will want the outside blocker to get the high foot into the defender's crotch and have the inside blocker basically fill in behind that outside blocker and push him through. Others want the inside blocker to engage first, targeting somewhere between the inside number and the middle of the chest of the defender, and then while the defender is engaged with the inside blocker, to have the outside blocker push through the hip or love handles to push the defender inside. Regardless of your way of getting there, what you don't want is the inside and outside blockers working against each other, or in other words, one pushing one way and the other the other way.

Lastly (in this very general sense) one of the combination blockers will come of that combination block and go block a second level defender to the backside of the play. As I said, typically we want the outside blocker to leave to the second level, because that is the preferred angle to the defender to seal him backside. But that can all change based on how patient it is preferred for the combination block to be (do we emphasize sealing the backside as far back as possible, or do we emphasize winning the first level first?), how the LB reacts (does he plug, does he scrape over the top?), how the DL on the first level reacts (does he slant inside or outside?).

Lesser Utilized But Still Important Combination Blocks

The first two of these really aren't that different other than it's just different players executing the combo block.

A "Quad" block is a combination block between two front side Tight Ends (or the third and fourth blocker to the side of the Center in the case of Tackle Over) to a backside defender.

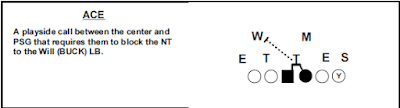

An "Ace" block is a combination block between the Center and Guard to a backside defender.

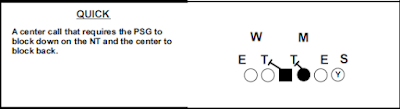

Block Back and the Act of Playing Slow

One of the most underrated difficult assignments in football is blocking back. You think, it's just like a down block or just pinning a guy to the backside until you realize you have to avoid the puller that's going opposite, you have to prevent player from winning over the top of you, but oh yeah, you also have to prevent the guy from grabbing onto the puller's butt and riding him straight to the ball. Usually you have to do this after snapping. This is often called a "Choke" block, because you are helping to choke out the hole left by the vacated puller.

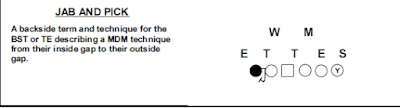

But there is one technique or call that I want to focus on that is a bit unusual, one we call a "Slow" technique. Why is it called slow? Because you slowly work back after first helping with a defender head up from you. So if the LG is pulling and there is a 3T outside of him, but there is also a NT in front of the Center, the RG and C will execute a "Slow Ace" block. Ace means it starts off as a combo block between the RG and Center, "Slow" indicates that the C is going to release (relatively quickly) back to a backside DL.

Pulling Out the Stops

Again, a lot of ways to skin a cat here. Some teach skip, some teach traditional pull, but the end is pretty much the same. The puller likes to read the inside arm pit of the intended kick player. The arm pit doesn't lie. Either it turns to you, and he's trying to wrong arm/spill (and you log), or it stays square and he's trying to log. Now, a more modern technique called "dent" in the last few years makes that read a little more difficult, but nevertheless, that's the plan.

Kick Block

The path needs to be flat and tight to the LOS. If you err, err on the side of upfield, because the defender going deeper into the backfield is mostly fine, he'll take himself out of the play. We want a kick out block to be a collision, it is a violent block. But it isn't an out of control block (or you'll fall on your face). So come to balance and collision with the outside, solid part of the shoulder (so if you're pulling right, your right shoulder). Upfield foot (left foot when pulling right) is where your power is generated, should be at 90 degrees to the target. We try to get under their shoulder and strike out and up to root them out. That arm should be tucked in so as not part of the collision, but post collision can be used like a flipper or crowbar to help lift the defender. Naturally upon string, your arm not within the strike will wrap around on the defender to prevent him for fighting back up field.

Log Block

The initial path remains consistent, however, now the defender has turned to square you up. Imagine you are in a race around a basketball poll and back. When you go to round the basketball poll, you're not going to just circle it at full speed because your path is too round. You're also not going to reach the poll and then pivot around your inside foot to run the other direction. When you do that you artificially lose speed and your power is generated through that pivot foot. Instead, you are going to reach out and grab the poll and use that as your pivot point, whipping yourself around. A log block isn't too much different.

On a log block you want to contact through the shoulder that is deeper in the backfield, keeping your inside hand slightly lower and preparing to wraps around a bit higher with your outside hand. The collision is still present because the collision slows you down so you can turn the corner, but it also forces the defender to react to on-coming force, making it easier to hook him. As you use the defender as a pivot point, as you would when rounding the basketball poll, or as you would when rolling on a log. Now, when rolling on a log your chest stays square and tight to your pivot point. That's how we want to round the corner, keeping our feet back, chest tight, to maintain generating power as we whip our butt around. Once we get our butt around, drive the hips in and lift and drive the defender back into the wash.

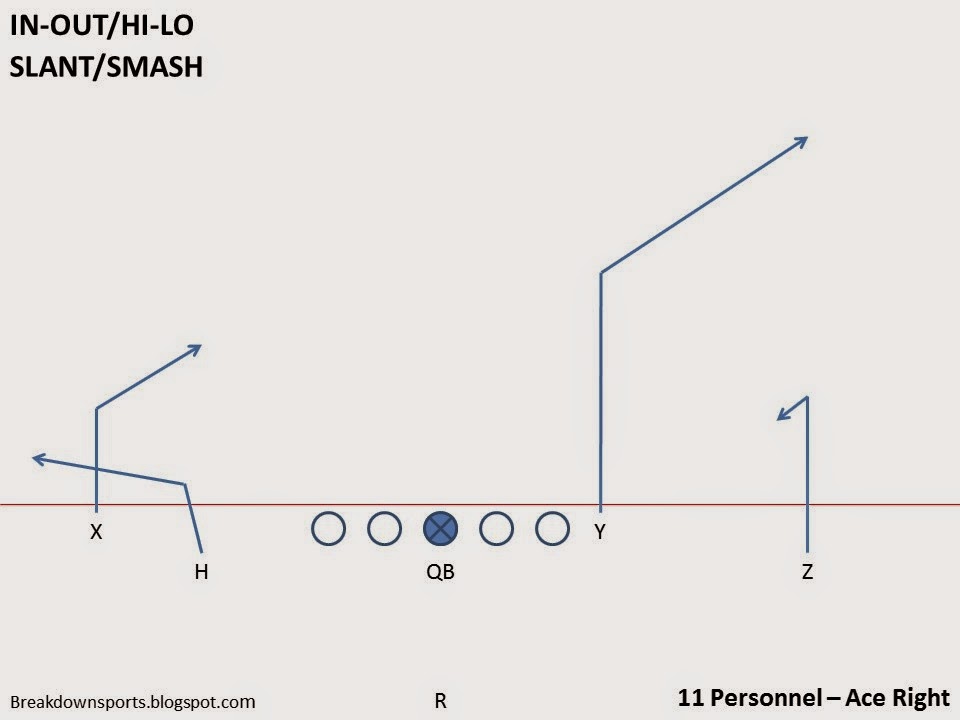

Lead or Wrap

On a lead or wrap block, we generally want to meet the defender with our shoulders square. However, upon arrival, we want to clear the head based on the reaction, path, and position of the defender. But regardless, you want to impact first with shoulder (it's a collision), then finish with either a flipper/lever from the shoulder side arm to lift up and out, or bring two hands. Hands general benefits block maintenance, but generally you may decrease a bit the force of the collision and it's difficult to latch onto the block anyway given the colliding nature of the block.

At All Hinges on This

Last of the blocks is the backside hinge block, also known as a Cutoff block, among other things. Step down to close the gap due to the vacated puller. Keep a wide base and rotate the backside foot back into the backfield to keep good play strength. Get square to the defender bring hands, lift with hands, bring hips, prevent the defender from squeezing the play down.

While Michigan did not execute this call, because they swapped the puller, there is an option to secure the backside DL while executing a combo up to the BSLB.

Mesh Point

Michigan implemented several mesh points and RB alignments.

There was backside sidecar:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) May 29, 2022

Open Opposite Counter OT (log) with Arrow RPO pic.twitter.com/Jv3WY7l68V

Frontside sidecar:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) June 4, 2022

Open Same side Counter OH pic.twitter.com/x4snlFmdKG

Deep Backside Sidecar:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) June 3, 2022

Strong Opposite Counter OF pic.twitter.com/vaN8fBPqR1

Deep Frontside Sidecar:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) June 3, 2022

Strong (TE-Wing) Sameside Counter OF pic.twitter.com/HjTFMOJmNW

Backside Pistol:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) May 29, 2022

Open Counter OH pic.twitter.com/hGdGVsAH8a

And Frontside Pistol:

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) May 29, 2022

Strong Counter OH with Jet motion pic.twitter.com/4o6uas5BnQ

Sweep

Counter Sweep. Blocking looks the same to the defense, but the pulling G will either log or bypass, there is no kick.

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

(Have mentioned it previously, but playside combo block also great here) pic.twitter.com/xQp69tmzM0

Handback

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) May 29, 2022

Open Opposite Short Counter OH (with Orbit RPO) pic.twitter.com/xkeO0bxYv5

BASH

Michigan

— TalkingDogBDS (@TalkingDogBDS) June 4, 2022

BASH Strong Q Counter OT pic.twitter.com/lfzgDJrC9V

Examples of Executing Various Techniques:

Michigan executing against a line slant to the play side.

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

Center and LG execute a Slow Combo block through the NT to the backside DE.

Front side Trey block doesn’t chase the slant, goes to seal pic.twitter.com/2XG8qsBIwp

Pulling the Center and dealing with a line slant: same Slow Technique from the G. Protect against the slant to the play pic.twitter.com/C32coDUkFd

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

Finally, short Counter OH.

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

Center reacts to slant a little slow, but eventually cleans up the backside slant with a Slow technique that can then climb once he has pushed the DE back onto the BST pic.twitter.com/1cYwsTOmOm

Counter OT from Michigan. See how the two pullers play at different levels.

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

Front side Trey (TE-OT) block is great. TE gets long, shoves the hip of the 4T inside to allow the RT to seal, climbs and cuts the D in half at the backside LB pic.twitter.com/PLxpXGQDaz

UM regaining numbers playside vs heavy 5T

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 30, 2022

Heavy 5 will look to spill the first puller while disrupting the combo block. This allows LBs to scrape over the top while playside interior gaps are closed.

So RT stays square and drives heavy 5T out, equaling blocking numbers pic.twitter.com/aW1Kq2NIaS

2 Look from OSU. LT stays square, let’s the DE attack, torques him inside. They go win the game pic.twitter.com/HP5NWmlnhl

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

Patience on the frontside. What is a presnap Deuce block sees the front side LB plug, and the LT stay square, pick up the plugger, and go win the game pic.twitter.com/3mXvW5Dp4p

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

Again a frontside Deuce block without a gallop technique. But watch how the two work together to throw the 3T inside and climb to the backside LB pic.twitter.com/r8RLcqjyON

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

Another great example of a gallop technique by the RT.

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

And check out the kick by the H pic.twitter.com/OhlTB4DrZd

Protect the scheme and execute

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

Pull C because backside 3T

C gets on edge fast. Edge should spill but isn’t prepared for speed

Gallop technique by LT on Deuce (OT/OG) block climbs right to backside LB

Watch to the end to see the perfect view of a defense split in half pic.twitter.com/8NamEHINM6

Now let’s look at the combo block. Patient. Let’s the defense over pursue. Then washes by pic.twitter.com/2ElW2RQfwM

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) August 29, 2022

Conclusions

Execution is fundamental in football. But it is not alone. In the last portion of this series, we will look at how Michigan protected the counter scheme with their playbook.

Comments

Post a Comment