Inside the Playbook: Bluff and Go RPO

Introduction

At the college (and high

school) level, RPOs continue to grow more and more challenging to defend. With

relaxed rules against linemen downfield, defenses have been forced to maintain

coverage longer and longer following the mesh point. No play demonstrates this

more than the “Bluff and Go” RPO.

Origins – Zone Read

When the zone read first

took off, it was as simple as running zone one direction, reading the backside

end, and defenses being completely lost in how to defend it.

But they quickly

figured out: if you want the QB to give, all you need to do is keep the DE from

chasing. If you want to trick the QB into keeping, you run a scrape exchange (or other front game).

|

| Smart Football |

There were two main ways to

mitigate the defense from dictating the offense. One was to run a version of

the triple option, allowing the QB to always be right. We’ll come back to this. The other was to start utilizing an

“arc” block to be able to more effectively block the ways defenses were trying

to trick the QB’s reads.

This Arc Read has become a staple in the past few years in football.

And as defenses adjust, so

do offenses, sending as many as two lead blockers out of the backfield as

spread elements continue to find their way into condensed and heavy formations.

GAP READ (not ZONE READ) ... is the foundation play in the RAVENS RUN OFFENSE. #1 player leads for ALLEY (here the WR in short motion) and #2 player blocks FSLB (here the TE in backfield) while the OL GAP BLOCKS (double teams) backside. pic.twitter.com/jM8Qw2TNH2— Paul Alexander (@CoachPaulAlex) March 26, 2020

Origins

– Screen Action

In the early 2000s, Rich

Rod brought back the triple option off his new zone read staple.

But not wanting to be forced into a two-back offense, he

modified the “pitch man” into bubble screen as

part of a triple option RPO package. With the field stretched out, the bubble

man became the pitch option, with WRs to his side of the field acting as the

outside blockers for the DBs outside the “pitch read” defender (typically an

apex type defender).

As more and more teams

implemented the bubble screen back into their offense, particularly as an add

on to the run game, you started seeing safeties attack the bubble downhill to

re-equalize numbers on the outside after the QB read the apex defender.

|

| Fish Duck - As teams got beat by bubble more often, they started shooting down safeties on bubble action or immediately chasing bubble action with their Apex Defenders, or both. |

The natural offensive

reaction to this defensive answer is similar to the concept of Play Action, in

an idea I often call “Screen Action”. On the outside, the initial movements are similar to

what you would see on the typically screen play, only to fake that action and

move into pass routes.

Screen action works with a variety of WR screens as well. I'll come back to this in a future article.

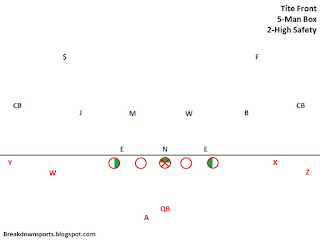

RPO Bluff and Go

The first time I recall

seeing this concept was Ohio State vs Michigan State in Week 6. While I’m sure

this is far from the first time it was run, it was a very interesting concept

as MSU was trying to incorporate their CBs into setting the edge to defend the

QB run.

Here, the Buckeyes are running effectively a double post - wheel concept. The Spartans, using the CBs in more of a Cover 2/Trap fashion, are playing with outside leverage and eyes in the backfield. #3 and #1 are both running posts to block the safeties. Meanwhile, #2 bluffs out to the CB as if to clear the lane between the MSU Apex defender and the CB. As soon as the CB gets caught with his eyes in the backfield, the WR turns downfield and gets vertical to the vacated area behind the CB and outside the safety. A good use of a staple post-wheel concept.

Note here though that the OL is not run blocking. This is not an RPO with the RB. The only run-pass option on this play is the wheel or QB run, with the backfield action serving as Zone Read Play Action.

A week later, both

Illinois and Michigan would run variations of the same concept.

First, Michigan. Here,

Michigan comes out 3x1 12 personnel. They run what is their typical arc zone

look (which itself is a sequence off of split zone)

The nub TE initially bluff

a block on the DB to the outside. When the DB jumps outside of him, the TE rips

upfield and runs a corner route.

What is nice about the nub

formation is that it often forces known adjustments from the defense. This

adjustment may come in the form of formation (“flip”, in which the CB follows

the WR to the opposite side of the field while the safety now has the outside

receiver in nub, or “invert” where the safety comes up off the edge as more of

a run defender and the CB goes to safety depth) or personnel (CB now responsible

for setting the edge vs run).

Here, the DB aligned to

the nub clearly is forced into setting the edge vs run, and jumps up against

the TE to maintain outside leverage. With only a single high safety deep MOF,

he’s stuck worrying about run, equating numbers due to the QB run threat, and the

two-WR side of the field. All these things mean his priority isn’t going to be

helping over the top of a TE, especially one that is working away from him.

Note: The offensive line is run blocking (perhaps a little too much), and give is an option.

Note: The offensive line is run blocking (perhaps a little too much), and give is an option.

Notice the QB, following the mesh point, works directly horizontal if not initially a little backward, similar to a roll out. This path gives him distance from the DL and also time to force the CB to commit to either coverage or stepping up to the run (ie it extends the QB’s time to make a read). In these cases the QB is really just reading the DB over the receiver for pass/run, with the possibility to check the deep safety to make sure he isn’t working over the top.

What’s nice about adding

the arc block can be seen when Michigan apparently tried to run this concept

earlier in the year. Here, the CB continues to gain depth, and the WR can never

reduce the gap enough to bluff and go. No problem, as the offense still has the

lead blocker on the edge to execute an effective QB run plan.

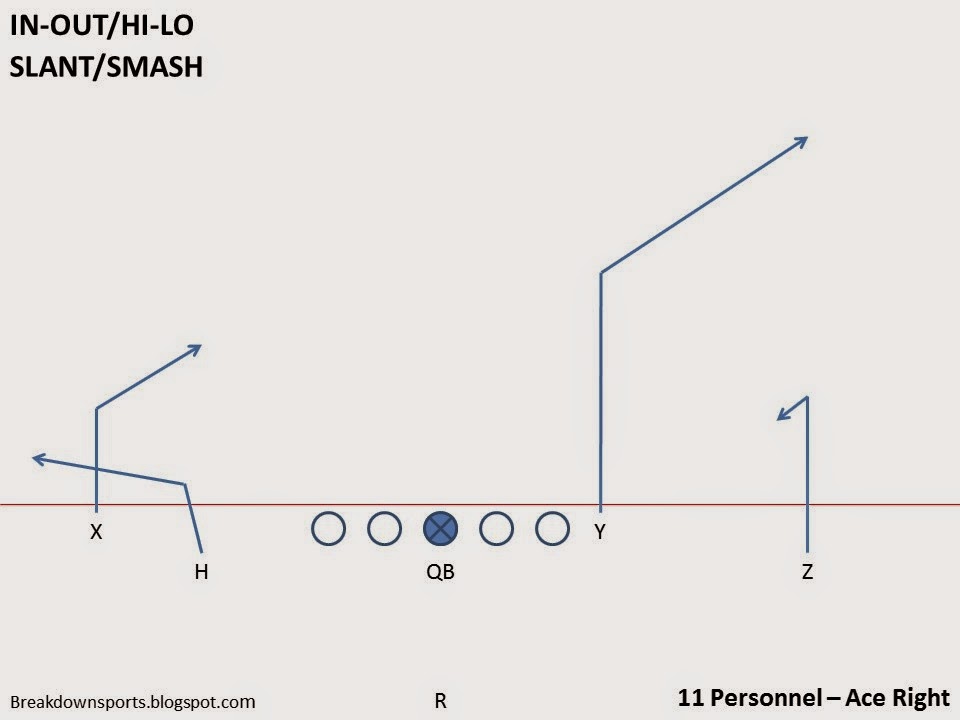

Illinois comes back later

with a similar concept, but with a WR split out.

Here, the WR bluffs the

stalk block on the CB. The CB gives him an inside release, and the WR runs a

streak. The inside release makes the angle of the pass significantly more

difficult, but the WR is able to get plenty of separation from the CB in order

to bring down the pass.

I do like the addition of the bubble to the top of the screen. It does a lot to both hold the field safties in that direction, but also to pull the LBs in that way. Vs a two-high coverage, you are likely to see the boundary safety help in run support on the QB, so pulling the rest of the defense to the field can be a significant benefit.

I do like the addition of the bubble to the top of the screen. It does a lot to both hold the field safties in that direction, but also to pull the LBs in that way. Vs a two-high coverage, you are likely to see the boundary safety help in run support on the QB, so pulling the rest of the defense to the field can be a significant benefit.

Interestingly, Michigan

came back to their Arc Zone Bluff and Go RPO vs MSU.

Here, similar to Illinois,

they run it out of 3x1 to the field, with the single receiver side being a

split out WR. Unlike Illinois, the WR’s split is condensed. This helps

significantly. As the WR goes into his stalk block, he is able to gain width

and has more spacing to the sideline. As he engages in his block and the CB’s

eyes start cheating into the backfield, the WR is able to rip and gain the

sideline, making the QB’s passing angle significantly easier, and Michigan gets

an easy TD.

The last bit comes against

OSU in the last game of the year. OSU, down their nickel CB, reverted to what

they call their 4-4 defense. When Michigan went TE-Wing in 12 personnel, the CB

would flip to follow the WR. This meant LBs had edge responsibility vs this

formation.

To put those LBs further

in conflict, Michigan runs a split zone concept, making the OLB to the boundary

the edge defender against split zone look. The RPO adjusts to opposite the RB’s

alignment. By the QB watching the deep safety, he can be confident if the LB is

getting help over the top. Without that help, he knows it’s at worst a LB 1v1

vs his TE, and at best the LB in conflict with the run giving separation to the

TE.

Furthermore, the TE-Wing

formation allows for the inside TE to be the one to release into the formation,

which regularly causes coverage issues for defenses as teams are forced to

defend receivers with inside LBs rather than the edge players, who are

especially stressed by the run key that is the outside TE.

The TE position also acts

similar to the “condensed” WR split, giving a lot of room to the edge. Here,

with the edge defender off the LOS, the TE can stem to him as he would on his

zone block. That stem allows him to work to the edge, giving him the Go route

down the sideline rather than the corner route.

Great scheme play by Gattis. He knew OSU formation check vs 12P Flank was to play “Flip” coverage with corners over. Puts the LB in an unusually run fit/conflict. https://t.co/WhtiSK5xtf— James Light (@JamesALight) November 30, 2019

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteOsuppviZna_ri2000 Chris Lemons link

ReplyDeletetiocounsuncvi