Inside the Playbook - Michigan State 3x1 Counter OT vs 2-High Coverage

Against Northwestern's primarily two-high defense, Michigan State found a wrinkle that was effective for their run scheme out of a 3x1 formations (three receivers to one side of the formation, one receiver to the other side). Primarily a zone team, MSU attacked the Wildcats with a mix of Zone Windback and Counter OT. Let's take a quick look at their use of Counter.

The Play

MSU

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) February 9, 2022

Counter OT is great vs teams that try to get gapped out off the edge (rather than from safety depth). NU stuck with 2 defenders backside (would like DE to work over top knowing LB has backside)

Good log block by LG. Good patience by RB to give space from wrapper to read pic.twitter.com/yM1YEPqIow

Background

Counter OT has seen a bit of a resurgence the past decade, after mostly falling out of favor by the early 2000s. Even before the world of spread football took over, Counter OH/OF had become preferred, utilizing the backs speed to get to the point of attack quicker. But in a world of 10 Personnel and 4-wide, teams wanted again to find a way to add two gaps to the playside, and couldn't get there in the RB run game without pulling two OL.

The first team I recall bringing back Counter OT as a base play was the Lincoln Riley Oklahoma units. Incorporating the read element to "block" the backside DE, they were able to pull two OL without having to bring numbers back inside the box (or in the event they did utilize an H, utilizing him instead on RPO routes such as Slide RPO). This allowed them to gain numbers back in the run game while also adding two new gaps playside.

Today, it seems as if most teams in college football at least have Counter OT in the playbook. It's typically only ran a few times per game at most, but it serves as a nice changeup for teams. Michigan State is one of those teams that use it, with QB Payton Thorne being a sufficient run threat to hold that backside DE.

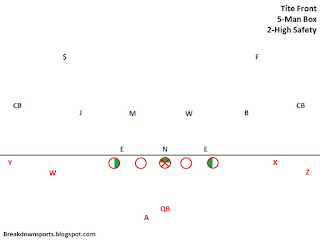

3x1 Formation vs Two-High

One of the primary benefits of a 3x1 formation against Two-High defensive structures is that it will cause the defense to rotate to the passing strength. This allows the LB to apex or even go over the #3 receiver, and truly provides a 4 over 3 that the defense is looking for. But especially if the RB is aligned to passing strength, giving a 4-strong pass threat, the LBs really need to shift to be able to account for the pass threat.

What this means is that to the single receiver side, typically a defensive back will have to have run fit responsibility. In general, this is a win for the offense, and one of the primary reasons teams like to run to the single receiver side. Running it to the boundary also often supports the angles.

Now, with the two-high coverage structure, rotated LBs and the ability to read the backside DE, you can effectively put 5 defenders to the backside of the play with only 4 blockers (that includes the QB), which effectively leaves you 6 blockers on 6 defenders playside with Counter OT.

How Northwestern Tries to Defend

Most modern defenses, especially two-high defenses, prefer to spill. Some will do either, depending on the coverage structure, run support, and offensive formation, but in the world of spread offense, spill defense rules supreme.

Generally speaking, as LBs tend to be smaller but faster in modern football, spilling allows them to play fast rather than have to take on blocks from OL head on. But besides just forcing the offense to play more east-west than north-south, spilling benefits two-high teams because it allows defensive backs to have run fit responsibilities off the edge.

This is good, because it more closely mirrors how defensive backs execute their run pursuit technique, playing things outside-in, rather than having to learn new techniques akin to a linebacker taking on a ball carrier in the hole. It also allows defensive backs to play their pass responsibilities longer before reacting down to the run. This is important, because one of the cheap ways defenses try to gain back numbers to the weakside of the formation is changing who that last fill player is: the safety or the CB.

Certainly, the safety has an angle to fit inside or outside, though outside is generally preferred. But the CB, unless blitzing, will be challenged to fit an interior gap. Spilling keeps things consistent for the defensive front while being able to manipulate the backend and hopefully gain back a number by making the WR uncertain. This is why you see a lot of Cloud (cornerback force or cornerback in the run fit) to the weakside of 3x1.

The second thing the Wildcats are trying to do is overlap with the LB. The intent is that the wrong arm technique forms a pileup of bodies, and the second puller is then unable to wrap around that pile and get to the LB. However, from the LB's initial position, and with the threat of 4-strong, it becomes a fairly long path for the LB, and if that second puller is able to get to him, it is very difficult for the LB to anchor down (hold his position) without getting washed out, and a big gap forming inside of him. Again, there is a run fitter outside of the LB from a DB, so the LB wants to play tight to that wrong arm and force the ball to bounce back and outside if he can. If he comes around too wide and gets washed down, no one is there for the tackle.

How Michigan State Blocks Northwestern

Northwestern is, in fact, in Cloud support. However, the DB starts wide and from depth. This help force the WR release inside in the pass, which supports the safety, but against the run, it allows the WR to take a really nice angle, feel the CB's eyes working toward the run fit, and block him rather than push-crack to the safety. The WR in this case always wants to block the primary run support defender from the secondary, and this is really well executed by the WR here.

The guard does well to see the DE surfing down inside. Because the DE isn't working up, the OG stays on his track, latches onto his upfield shoulder, and then "logs" him. This means he literally punches through the DE's shoulder and rolls over him like a man hugging a rolling log, sealing him inside.

The OT does well to keep some separation from the OG. A lot of guys want to get right up on the back of the puller in front of them (RBs included), even touching them with their hand. No! Keep some space so you can read that block and react properly. Here, the OT sees the OG log the DE, and then is able to bow out and around that mass of bodies so he can get to the LB. That LB, for his part, is still scraping to get to his spot, and by the time he gets there, the OT is able to get just enough to wash him outside.

Note, the RB does really well to set that block up before cutting up field, understanding the flow of the defense.

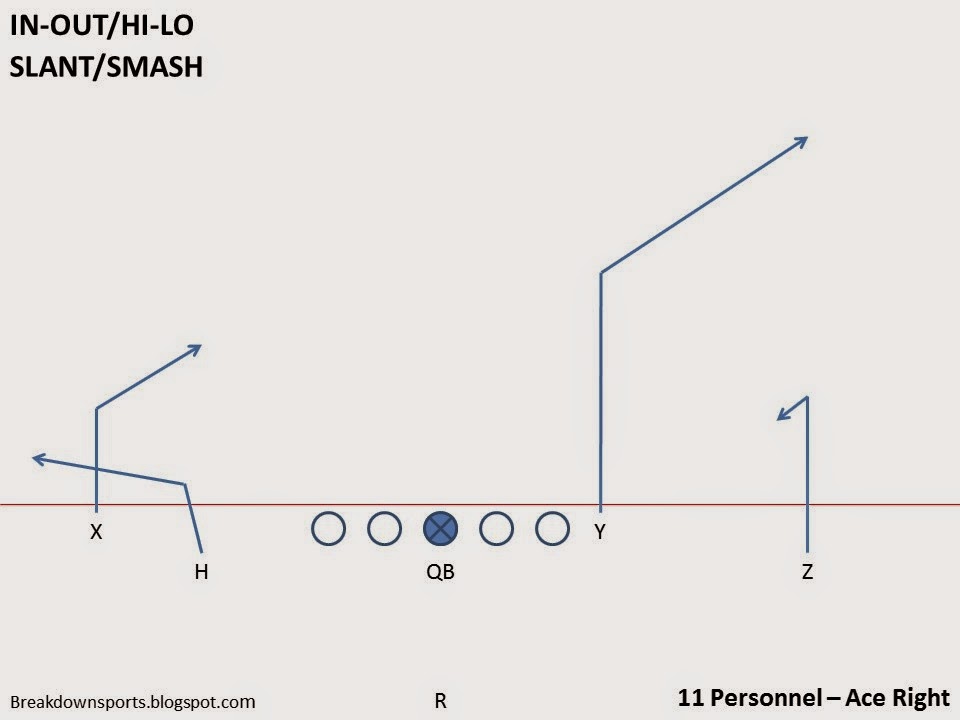

But This Play Could be More Explosive

This is the first game of the season, so take it as a learning opportunity. But formation and scheme here allow MSU to be hat-for-hat playside, but they don't take advantage of that. Rather than going true hat-for-hat though, they could focus on getting movement and could really mash on the front side. The way it's executed the combo is gone almost immediately as the PSG races to the backside of the play, and as such, the OL that releases on the combo kind of ends up in no man's land, and possibly limits the play. Be patient on the front side and really generate a punishing movement up front to cut the defense in half.

Typically, the backside DE should be doing better here because he does have the LB in that same gap when the OG and OT both pull. You would want him to try to chase the second puller to the ball or scrape over the top; that's better defense. But mashing that frontside double still allows the OG to help in those situations, because he's staying playside with eyes to the backside to pick up loose change. Be patient when you don't have an immediate target to go get.

Alternative, and more in line with how the Spartans tended to operate this year, is to alter the combo aiming point. Because the backside LB is so far backside, he really isn't a threat to the run. What this allows is for the blocking scheme to shift one to the playside. How do we accomplish this?

The combo block becomes more North-South, rather than East-West. In this case, the combo is trying to work to the playside LB. The Guard will still kick/log the DE, the WR blocks the safety, and the pulling OT blocks the first free color (typically the CB, but if the LB escapes the combo, he'll pick him up). This is a little more risk oriented, but it leaves you blocked fully on the playside, and if you get a two-for-one with the WR blocking the safety, you can really spring an explosive. Note also, there is a tendency to rush the combo to cut off the LB. You really don't need to do that. If the LB is in a rush, release and wash the LB past the play. Generate your movement up front, and get your hat-on-hat.

Northwestern Response

Later in the game, MSU again tried to run Counter OT to the single receiver side. This time, Northwestern aligns the CB head up on the WR and blitzes him off the edge and they come away with a tackle for loss.

MSU

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) February 9, 2022

Another example of Counter OT where patience in the front side combo will help them. Northwestern sends boundary CB blitz. This means DL is slanting away. No need to hurry to 2nd level, RT stay square early, let DE cross face and wash him down. Then BSG kicks CB and big play pic.twitter.com/vR7V5b1sf0

But this is why you block it with one of the alternatives above. MSU gets great push on their double, but they are releasing to a backside LB that won't make an immediate play. This results in them not being patient with the front side double, which would still be able to release to the backside LB if needed, but also allows the OT to be more patient, and potentially turn the DE inside (if he really tries to fight inside and the OT stays square to the LOS, as he should) and or at least really generate strong seal to open up the inside run lane a bit more, rather than forcing the ball to bounce.

Alternatively, a north-south combo allows the OT to work to the CB, knowing that someone is already working to the ILB.

Comments

Post a Comment