Inside the Playbook: Sequencing to the Throw Back

In offensive football, we often talk about the act of "sequencing plays". What this means is that we initially build a base play. Once a defense does something unsound to stop that base play, we "sequence" a "constraint" play designed to take advantage of that unsoundness. Once the defense responds to that "constraint", we further the iteration to take advantage of that response. In this post, we are going to look at the sequence of events that leads to running throw back plays.

|

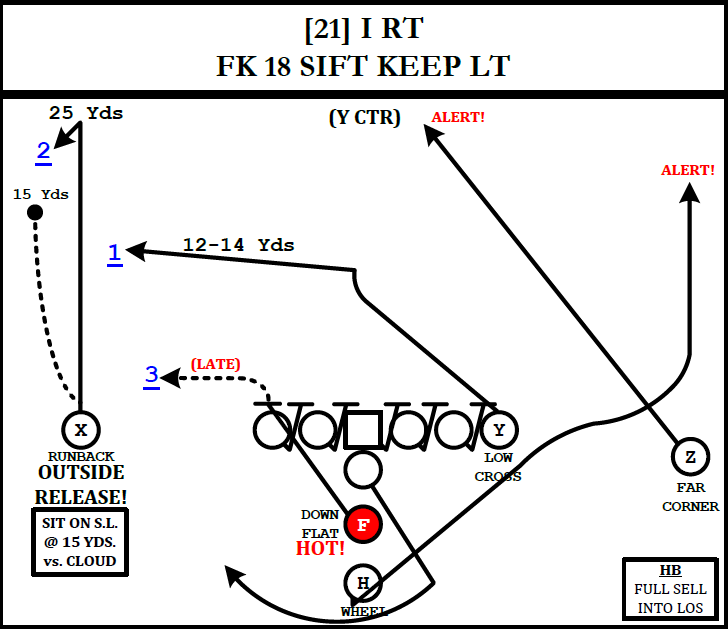

| 2014 Falcons Playbook - Sequencing |

Establishing a Base

In this sequence of events, the base play is traditionally a run play. Whether that play is stretch or power or counter, that initial run play forces a defense to react horizontally. Against wide zone, the defense has to pursue laterally to match the gaps moving the direction of the zone blocks.

Against gap plays such as Power and Counter, the defense (specifically the backside of the defense) has to react horizontally to match numbers of the pullers and lead blockers.

Now, personnel and formation can change how the defense is played. How many defenders will be dedicated primarily to coverage vs how many defenders have immediate run-fit responsibilities. It can change a defense from playing a 7-man spacing idea to and 8-man or 9-man spacing idea. In more generally terms, is there a defender for every gap, including the QB run (9-man spacing), or is the defense out-numbered in the run game (8-man spacing down one gap vs QB run; or 7-man spacing which is down at least a gap against any run)?

But, for the purposes of simplification, the offense generally has 9-blockers for 11-defenders (the QB and the ball carrier don't block). Offenses try to win that back in a few ways:

1) Perimeter blocking - Crack-Push blocking will ask a WR to block a most dangerous defender while leaving a secondary run support defender unblocked (the defender in man coverage, or a defender primarily responsible for a deep zone), and preferably, take two defenders with him when he makes his block. A crack block itself will often pull in a man-coverage defender who isn't prepared to put himself in the run fit. A gain block is going to leave the outside CB away from the play unblocked, because he's so far away from the play and a CB, so why wouldn't you.

|

| Iowa Playbook - Example of Gain Block and Crack-Push |

An example of a poor crack exchange, the crack blocker taking the man coverage with him while he blocks a LB/DE

Taking advantage of a whole suite of OSU tendencies while breaking your own = TD pic.twitter.com/LtobffTD3y

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) September 14, 2021

2) QB Reads - This is the case for both run-run reads (where the QB is a run threat) and RPO reads. But note, defenses have gotten smart. Where the idea is that the "read" acts as an additional block to gain back numbers, defenses can do a few things to combat that:

a) They can make the reads wrong, such as executing a scrape exchange.

| Smart Football |

b) They can make a read non-existent, such as the use of man coverage on the outside against an RPO or taking the read defender completely out of run fit responsibility.

c) They can set their gap fit responsibilities to keep the defense in "manageable conflict". What this means, for instance, on the backside of an RPO, have the conflict defender responsible for the outside gap to the backside. This gap will take longer for the offense to reach as it's toward the outside and the backside of the play, giving the defender time to read the mesh point and then respond appropriately.

3) Leaving backside defenders for the wash. Often times, apex defenders or backside defenders are too far away from the ball and have to work through too many blockers to legitimately make a play on the ball at the point of attack. Those players can prevent nice gains from becoming explosives, so you still prefer to account for them in some way, but they don't necessarily need to be blocked for the play to be successful.

|

| The Jack here is unblocked and not part of an RPO read |

4) Motion. Motion, either from backs or from receivers can simulate new run threats and shifting of strength/gaps. Via the immediacy of this threat, you can often capture 2-for-1 impacts by making good use of it.

5) The bootleg pass.

The Bootleg Pass

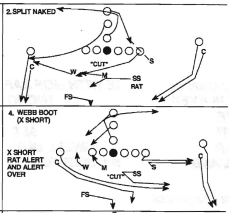

The bootleg pass is a way of simulating the run action of your base run plays, and then rolling the QB away from the run action after he simulates the hand off. For a QB who is a run threat, this stresses the backside edge of the defense by putting an athlete in space. But even for QBs with limited athleticism, this acts as a constraint for the defense. How?

|

| 1998 Wisconsin Playbook |

Even with limited athleticism, is the defense doesn't account for the QB, the QB has so much space and so much time that he can pick up yards while the coverage tries to stick to receivers. But generally speaking, this also impacts the defense simply because of the pass threat.

Bootleg passes generally operate in three ways: 1) 3-man levels concepts; 2) Triangle reads; 3) A combination of the 1) and 2). What this means, is it generally puts three or four receiving threats to one side of the defense.

OSU

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) February 4, 2022

Power of condensed formations is ability to add numbers to the opposite side of the formation. OSU finally goes to boot (instead of throwback) with a 4 man flood.

Notice how crosser from the backside makes sure he stays at a different width. Keeps triangle and spacing pic.twitter.com/aTaYtC9wfc

For zone defenses, the further you are away from the ball, typically, the more area you are responsible for covering. This generally makes sense, the further from the ball, the longer it takes the ball to get there, the more time you have to react and defend the pass. But as the ball moves to the edge on the bootleg, those zones responsible for covering larger amounts of area are now moved closer to the ball. On top of that, they are no longer protected by the underneath defense who obstructs the view of the QB and can bat down low-trajectory throws. What this effectively means for defenses is they need to roll their coverage in the direction of the QB to reduce those windows while simultaneously trying to force the QB to get the ball out with a force defender before the coverage breaks down.

For man coverages, the difficulty comes in terms of leverage. Man coverage is designed with the idea of "help" in mind, and indeed, the leverage of the coverage is based on where that help is, but also where the ball is. For instance, in Cover 1, outside defenders align with inside leverage because the inside help is close enough to actually support them; so instead they use the sideline as their support. But inside coverage typically aligns with outside leverage, because the inside defenders have help to the inside. But if you change the position of the ball with the QB, this changes the leverage of the defense, and the coverage defenders often have to work to try to get back in appropriate leverage post snap.

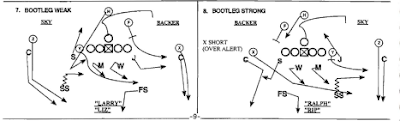

Getting Outside the Defense vs Leveraging the Offense Inside

The goal of the bootleg play is for the QB to get outside the defense and threaten the edge. On the edge, the QB now has shorter throws to the sideline without the downside of having to work through the offensive and defensive line. Without a leverage defender, the defense is left chasing the QB, trying to get to him before he can run the ball, or doing something unsound in coverage with a defender in conflict trying to play the run and pass (effectively, an RPO).

Now just like Zone Read, the defense has a few answers for ensuring they have leverage on the backside. The simplest answer is just "keep the backside defender home". This sounds great, until the RB cuts back, and that defensive end, who is a good run defender, is stuck playing grass worrying about a bootleg rather than defending the run. You hope he can play both, but if something happens to say the DT inside the DE gets washed down hard, that grass can be too much for even the best space players to defend.

So the answer to this problem in zone read parlance is gap exchange or two defenders to the backside of the play.

Bama has a beat on opening boot play. But WR sits in the throw window. Gotta get to the sideline earlier to give the QB options pic.twitter.com/fGpAIQuuWA

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) January 18, 2022

Michigan

— Space Coyote (@SpaceCoyoteBDS) February 7, 2022

Defending boot action with 2 off the edge from Cover 1 pic.twitter.com/aZB8uqEygG

This allows one to chase and the other to stay home. This is all well and good, because the defense is now gap sound, but the defense has also now dedicated a defender specifically for the QB and away from the RB run game and limited what the defense can do in coverage.

Lastly, we can talk about "Dash Replace." Many bootlegs retain a backside blocker (a TE or RB) responsible for protecting the backside edge and ensure the QB isn't immediately threatened while trying to sell the run action (the exception being naked boot) and can break backside contain. To counter that, once boot action is confirmed, a defender (typically a LB or a safety) that was initially part of coverage structure, will sprint to get outside the rolling QB to set the edge, while the defender that was blocked by the "dash blocker", will be responsible for coverage if that block was to release.

|

| San Francisco Defensive Playbook - Cover 1 - Dash Replace - Note, if F has a delayed release, the SAM needs to cover or they need to have a different game plan. |

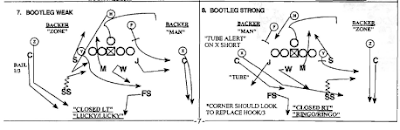

Rolling the Coverage

So we've touched on what the front will do to try to speed up the QB and prevent him from being a run threat, but there is still the issue of the backend in coverage.

In zone, the zone defenders are typically going to roll their coverage. The underneath defenders will will toward the sideline and slide over a zone, often attaching themselves to crossers rather than covering grass.

Deep defenders will often push rotate the coverage to the rollout. For example:

- A deep 1/3 defender will change to man coverage.

- A middle-of-field player will become a deep 1/2 or middle 1/4 defender.

- A backside 1/2 player will match the crosser or become a MOF player.

- And a deep 1/3 player on the backside will become a deep 1/2 player.

In man coverage, the backside defenders will try to work to gain back their leverage, getting underneath and inside the receivers to stay between the ball and receiver, like basketball. The ball is moving, so the relation to the defender needs to change to maintain that position.

The defense then has the option of how they want to maintain responsibility away from the rollout. But typically, it will be one of three ways:

1) Deep zone player watch for throw back;

2) A dedicated "throw back" defender.

3) A combination of 2) and 3)

|

| 2008 49ers Defensive Playbook |

|

| 2017 FSU Defensive Playbook |

|

| 2006 Miami Dolphins Playbook |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - 1 Buck |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - Cover 7 |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - 7 MEG/Switch (plays out same as 7 MOD/Fist) |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - Cover 8 |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - 9 Rat |

| ||

| 2006 Dolphins - 3 Auto |

|

| 2006 Dolphins - Frisco A TED |

| ||||

2006 Dolphins - Firezone

|

|

| 2014 Wisconsin - Dog |

It is the discipline of these players that the throw back is trying to test. Can they be trusted not to chase the ball to try to get into the play? Can they be trusted to know their responsibility in the coverage depending on defensive play call? Even if they stay disciplined, can they win the coverage match up or can they fight through the wash?

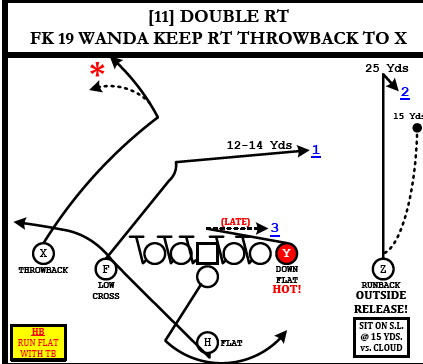

Sequencing the Half Roll Throw Back

So now we have the defense trying to set the edge on the backside, meaning they've dedicated a defender to try to account for the QB, and taking him out of coverage. The half roll is no longer trying to get outside this defender, instead, they are simulating the roll out only stop and allow the QB to set his feet. He'll need that, because he's throwing the ball back to the far side of the field.

The coverage, now seeing the bootleg action, as begun to roll. Whether it's zone coverage trying to reduce the area they must defender near the ball, leaving larger areas to defend on the backside, or it's man defenders trying to fight back for leverage, or it's "dash exchange" defenders trying to execute their new role within the defense that they didn't anticipate having pre-snap, the throw back will take advantage of it.

In the next post, we will look at the various ways offenses do this.

Clip w/ diagram of the Bears Throwback/Leak play off wide zone action vs MIA. Good blocking scheme wrinkle with the Center peeling back to provide protection on the edge. Y gets lost in traffic and springs wide open. Scheme goes back to the Mike Shanahan era Broncos. pic.twitter.com/TEvvUjdLAv

— XandOJunkie (@Spread_it_Out) August 18, 2021

Comments

Post a Comment